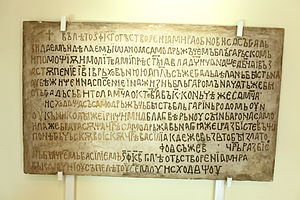

Bitola inscription

| Bitola inscription | |

|---|---|

The Bitola inscription | |

| Material | Marble |

| Size | 98 cm × 61 cm × 27 cm (39 in × 24 in × 11 in) |

| Created | 1015/1016 |

| Discovered | 1956 Sungur Chaush-Bey mosque, Bitola |

The Bitola inscription is a stone inscription from the First Bulgarian Empire written in the Old Church Slavonic language in the Cyrillic alphabet.[1] Currently, it is located at the Institute and Museum of Bitola, North Macedonia, among the permanent exhibitions as a significant epigraphic monument, described as "a marble slab with Cyrillic letters of Jovan Vladislav from 1015/17".[2] In the final stages of the Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria Ivan Vladislav was able to renovate and strengthen his last fortification, commemorating his work with this elaborate inscription.[3] The inscription found in 1956 in SR Macedonia, provided strong arguments supporting the Bulgarian character of Samuil's state, disputed by the Yugoslav scholars.[4]

History

[edit]

The inscription was found in Bitola, SR Macedonia, in 1956 during the demolition of the Sungur Chaush-Bey mosque. The mosque was the first mosque that was built in Bitola, in 1435. It was located on the left bank of the River Dragor near the old Sheep Bazaar.[5] The stone inscription was found under the doorstep of the main entrance and it is possible that it was taken as a building material from the ruins of the medieval fortress. The medieval fortress was destroyed by the Ottomans during the conquest of the town in 1385. According to the inscription, the fortress of Bitola was reconstructed on older foundations in the period between the autumn of 1015 and the spring of 1016. At that time Bitola was a capital and central military base for the First Bulgarian Empire. After the death of John Vladislav in the Battle of Dyrrhachium in 1018, the local boyars surrendered the town to the Byzantine emperor Basil II. This act saved the fortress from destruction. The old fortress was located most likely on the place of the today Ottoman Bedesten of Bitola.[6]

After the inscription was found, information about the plate was immediately announced in the city. It was brought to Bulgaria with the help of the local activist Pande Eftimov. A fellow told him that he had found a stone inscription while working on a new building and that the word "Bulgarians" was on it.[7] The following morning, they went to the building where Eftimov took a number of photographs which were later given to the Bulgarian embassy in Belgrade.[8] His photos were sent through diplomatic channels to Bulgaria and were classified.

In 1959, the Bulgarian journalist Georgi Kaloyanov sent his own photos of the inscription to the Bulgarian scholar Aleksandar Burmov, who published them in Plamak magazine. Meanwhile, the plate was transported to the local museum repository. At that time, Bulgaria avoided publicizing this information as Belgrade and Moscow had significantly improved their relations after the Tito–Stalin split in 1948. However, after 1963, the official authorities openly began criticizing the Bulgarian position on the Macedonian Question, and thus changed its position.

In 1966, a new report on the inscription was published. It was done by the historian and linguist Vladimir Moshin,[9] a member of the Russian White émigré, living in Yugoslavia.[10] As a result, Bulgarian linguist Yordan Zaimov and his wife, historian Vasilka Tapkova-Zaimova, travelled to Bitola in 1968.[8] At the Bitola Museum, they made a secret rubbing from the inscription.[11] Zaimova claims that no one stopped them from working on the plate in Bitola.[8] As such, they deciphered the text according to their own interpretation of it, which was published by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in 1970.[12] The stone was locked away in the same year and a big Bulgarian-Yugoslav political scandal arose. The museum director was fired for letting such a mistake happen.[13] The Macedonian researcher Ugrinova-Skalovska published her translation of the inscription in 1975.

In 2023 the German linguist Sebastian Kempgen made an optical inspection of the plate. He discovered a superscript on the stone, which had already been reconstructed with linguistic methods. However Kempgen has shown that it actually exists, but it is a mystery why it has not been discovered before him. He has supposed that the superscript was made from a second stonecutter. Kempgen has also deduced that initially the inscription was carved at least on two stone plates, set together horizontally, and not on a single plate. Some letters from the current inscription were written on a lost plate, located left to the present block. Furthermore, it showed that the Zaimovs had incorrectly inserted missing letters, following lines 8, 9, and 10 of the inscription. The scans showed that no text is missing following these lines.[14] In a subsequent presentation, Kempgen described the Zaimovs' reconstruction as implausible, especially the existence of the first row on a separate stone above. He noted that his study confirmed earlier criticism of the Zaimovs by Horace Lunt, especially that the text must have spilled over to a lost block on the left.[15][16]

Text

[edit]There have been preserved 12 rows of the inscription. The text is fragmentary, as the inscription was used as a step of the Sungur Chaush-Bey mosque. There are missing parts around the left and right edge and a large part on the lower left segment. In its current state, the following text is visible on the stone:[17]

1. ....аемъ и дѣлаемъ Їѡаном самодрьжъцемъ блъгарьско...

2. ...омощїѫ и молїтвамї прѣс͠тыѧ владч҃ицѧ нашеѧ Б͠цѧ ї в...

3. ...ѫпенїе І҃В҃ і врьховънюю апл҃ъ съ же градь дѣлань быст...

4. ...ѣж.... и на спс҃енѥ ї на жизнь бльгаромъ начѧть же і...

5. ...... градь с.....и..ола м͠ца ок...вра въ К҃. коньчѣ же сѧ м͠ца...

6. ...ис.................................................быстъ бльгарїнь родомь ѹ...

7. ...к..................................................благовѣрьнѹ сынь Арона С.....

8. ......................................................рьжавьнаго ꙗже i разбїсте .....

9. .......................................................лїа кде же вьзꙙто бы зл.....

10. ....................................................фоꙙ съ же в... цр҃ь ра.....

11. ....................................................в.. лѣ... оть створ...а мира

12. ........................................................мѹ исходꙙщѹ.

Text reconstructions

[edit]A reconstruction of the missing parts was proposed by Yordan Zaimov.[18] According to the reconstructed version, the text talks about the kinship of the Comitopuli, as well as some historical battles. Ivan Vladislav, claims to be the grandson of Comita Nikola and Ripsimia of Armenia, and son of Aron of Bulgaria, who was Samuel of Bulgaria's brother.[19] There are also reconstructions by the Macedonian scientist prof. Radmila Ugrinova-Skalovska[20] and by the Yugoslav/Russian researcher Vladimir Moshin (1894–1987),[21] In Zaimov's reconstruction the text with unreadable segments marked gray, reads as follows:[22]

[† Въ лѣто Ѕ҃Ф҃К҃Г҃ отъ створенїа мира обнови сѧ съ градь]

[зид]аемъ и дѣлаемъ Їѡаном самодрьжъцемъ блъгарьско[мь]

[въ Ключи ї ѹсъпе лѣтѹ се]мѹ исходꙙщѹ

[и п]омощїѫ и молїтвамї прѣс͠тыѧ владч҃ицѧ нашеѧ Б͠цѧ ї въз[]

[ст]ѫпенїе І҃В҃ і врьховънюю апл҃ъ съ же градь дѣлань бысть [на]

[ѹ]бѣ[жище] и на спс҃енѥ ї на жизнь бльгаромъ начѧть же

[бысть] градь с[ь Б]и[т]ола м͠ца ок[то͠]вра въ К҃. коньчѣ же сѧ м͠ца [...]

ис[ходѧща съ самодрьжъць] быстъ бльгарїнь родомь ѹ[нѹкъ]

[Ни]к[олы же ї Риѱимиѧ] благовѣрьнѹ сынь Арона С[амоила]

[же брата сѫща ц͠рѣ самод]рьжавьнаго ꙗже i разбїсте [въ]

[Щїпонѣ грьчьскѫ воїскѫ цр҃ѣ Васї]лїа кде же вьзꙙто бы зл[ато]

[...] фоꙙ съжев [...] цр҃ь ра[збїень]

[бы цре҃мь Васїлїемь Ѕ҃Ф҃К҃]В҃ [г.] лтѣ оть створ[енї]ѧ мира

Translation:

In the year 6523 since the creation of the world [1015/1016? CE], this fortress, built and made by Ivan, Tsar of Bulgaria, was renewed with the help and the prayers of Our Most Holy Lady and through the intercession of her twelve supreme Apostles. The fortress was built as a haven and for the salvation of the lives of the Bulgarians. The work on the fortress of Bitola commenced on the twentieth day of October and ended on the [...] This Tsar was Bulgarian by birth, grandson of the pious Nikola and Ripsimia, son of Aaron, who was brother of Samuil, Tsar of Bulgaria, the two who routed the Greek army of Emperor Basil II at Stipon where gold was taken [...] and in [...] this Tsar was defeated by Emperor Basil in 6522 (1014) since the creation of the world in Klyuch and died at the end of the summer.

According to Zaimov, there was additional 13th row,[note 1] at the upper edge. The marble slab bearing the inscription has on the top narrow surface holes and channels to fit metal joints. This is contrary to the Zaimov's claims that the inscription could have had another line on the top side.[23]

Dating

[edit]There is a single year mentioned on line 11 of the plate, which Moshin and Zaimov deciphered as 6522 (1013/1014). According to Zaimov, this date is relatively clearly visible,[24] although Moshin admitted that it has been rubbed.[25] Per the Slavist Roman Krivko, although the year carved in the inscription is unclear, it is correct to date it to the reign of Ivan Vladislav, who is mentioned as acting there, accordingly to the used present tense verb form.[26] The art historian Robert Mihajlovski one the other hand, puts the dating of the inscription in the historical context of its content, i.e., also during the reign of Ivan Vladislav.[27] The majority academic view, shared by a number of foreign and Bulgarian as well as some Macedonian researchers, is that the inscription is an original artefact, made during the rule of tsar Ivan Vladislav (r. 1015–1018), and is therefore the last remaining inscription from the First Bulgarian Empire with an roughly correct dating.[28] The Macedonian researcher to directly work on the plate in the 1970s, Radmilova Ugrinova-Skalovska, has also confirmed the dating and authenticity of the plate. According to her, Ivan Vladislav's claim to Bulgarian ancestry is in accordance with the Cometopuli's insistence to bound their dynasty to the political traditions of the Bulgarian Empire. Per Skalovska, all Western and Byzantine writers and chroniclers at that time, called all the inhabitants of their kingdom Bulgarians.[29]

American linguist Horace Lunt maintained that the year mentioned on the inscription is not deciphered correctly, thus the plate might have been made during the reign of Ivan Asen II, c. 1230.[30][31] His views were based on the photos, as well as the latex mold reprint of the inscription made by philologist Ihor Ševčenko, when he visited Bitola in 1968.[8] On the 23rd International Congress of Byzantine Studies in 2016, archaeologists Elena Kostić and Georgios Velenis based on their paleographic study,[32] maintained that the year on the plate is actually 1202/1203, which would place it in the reign of Tsar Ivan I Kaloyan of Bulgaria, when he conquered Bitola. They maintain, the inscription mentions some glorious past events to connect the Second Bulgarian Empire to the Cometopuli.[33][34] Some Macedonian researchers also dispute the authenticity or dating of the inscription.[35][36][37] According to the historian Stojko Stojkov, the most serious problem of the dating of the inscription from the 13th century is the impossible task of making any logical link among the persons mentioned in it, with the time of the Second Bulgarian Empire, and in this way the dating from the time of Ivan Vladislav is the most well-argued.[38] Velenis and Kostić confirmed too, that most of the researchers suppose that the plate is the last written source of the First Bulgarian Empire with an roughly accurate dating.[39] Per the historian Paul Stephenson, given the circumstances of its discovery, and its graphical characteristics, that is undoubtedly a genuine artifact.[40]

Legacy

[edit]

The inscription confirms that Tsar Samuel and his successors considered their state Bulgarian,[41] as well as revealing that the Cometopuli had an incipient Bulgarian consciousness.[42][43] The proclamation announced the first use of the Slavic title "samodŭrzhets", meaning "autocrat".[44] The name of the city of Bitola is mentioned for the first time in the inscription.[45] The inscription indicates that in the 10th and 11th centuries, the patron saints of Bitola were the Holy Virgin and the Twelve Apostles.[46] The inscription confirms the Bulgarian perception of the Byzantines (Romaioi) as Greeks, including the use of the term "tsar", when referencing their emperors.[47]

After the collapse of Yugoslavia, the stone was re-exposed in the medieval section of the Bitola museum, but without any explanation about its text.[48] In 2006, the inscription was subject to controversy in the Republic of Macedonia (now North Macedonia) when the French consulate in Bitola sponsored and prepared a tourist catalogue of the town. It was printed with the entire text of the inscription on its front cover, with the word "Bulgarian" clearly visible on it. News about that had spread prior to the official presentation of the catalogue and was a cause for confusion among the officials of the Bitola municipality. The French consulate was warned and the printing of the new catalogue was stopped, and the photo on the cover was changed.[49] In 2021, a Bulgarian television team made an attempt to shoot the artefact and make a film about it. After several months of waiting and the refusal of the local authorities, the team complained to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Sofia. A protest note was sent from there to Skopje, after which the journalists received permission to work in Bitola.[50]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Vasilka Tăpkova-Zaimova, Bulgarians by Birth: The Comitopuls, Emperor Samuel and their Successors According to Historical Sources and the Historiographic Tradition, East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, BRILL, 2018, ISBN 9004352996, pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Among the most significant findings of this period presented in the permanent exhibition is the epigraphic monument a marble slab with Cyrillic letters of Jovan Vladislav from 1015/17." The official site of the Institute for preservation of monuments of culture, Museum and Gallery Bitola

- ^ Jonathan Shepard, Equilibrium to Expansion (886–1025); pp 493-536; from Part II - The Middle Empire c. 700–1204 in The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire C.500-1492 (2008) Cambridge University Press, p. 529, ISBN 0521832314.

- ^ The Bitola inscription (found in 1956) of the last Bulgarian king Ivan Vladislav, son of Aaron (and nephew of Samuil), in which he defined himself as Bulgarian by descent gave strong arguments in favor of the Bulgarian cause. Roumen Daskalov (2021) Master Narratives of the Middle Ages in Bulgaria, East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450-1450, BRILL, pp. 226-227, ISBN 9004464875.

- ^ Present location opposite the trade center Javor on the left side of the street Philip II of Macedonia. For more see: Chaush-Bey Mosque – one of the oldest mosques in the Balkans (demolished in 1956), on Bitola.info

- ^ Robert Mihajlovski, Circulation of Byzantine lead seals as a contribution to the location of medieval Bitola on International Symposium of Byzantologists, Nis and Byzantyum XVIII, "800 years since the Аutocephaly of the Serbian Church (1219–2019): Church, Politics and Art in Byzantium and neighboring countries" pp. 573 – 588; 574.

- ^ Николова, В., Куманов, М., България. Кратък исторически справочник, том 3, стр. 59.

- ^ a b c d "Камъкът на страха, филм на Коста Филипов". Archived from the original on July 24, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Булатова Р. В. Основатель югославской палеографической науки — В. А. Мошин. В Русская эмиграция в Югославии. — М.: Институт славяноведения и балканистики РАН. (1996) стр. 183—199.

- ^ Битољска плоча из 1017 године. Македонски jазик, XVII, 1966, 51–61.

- ^ сп. Факел. Как Йордан Заимов възстанови Битолския надпис на Иван Владислав? 3 декември 2013, автор: Василка Тъпкова-Заимова.

- ^ „Битолския надпис на Иван Владислав, самодържец български. Старобългарски паметник от 1015 – 1016 година.", БАН. 1970 г.

- ^ Камъкът на страха – филм на Коста Филипов – БНТ.

- ^ Kempgen, Sebastian. "A Superscript for the Bitola Inscription (Bitolski natpis)".

- ^ Kempgen, Sebastian (January 2024). ""Marble, Stone and Iron Speaks". New Facts and Readings of the Bitola Inscription Based on a Digital 3D Model".

- ^ Sebastian Kempgen: A Superscript for the Bitola Inscription. Draft paper, 12, May 2023. Bamberg University, Germany.

- ^ Stojkov, Stojko (2014). Битолската плоча. Goce Delčev University. p. 80. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ Заимов, Йордан. Битолският надпис на цар Иван Владислав, самодържец български. Епиграфско изследване, София 1970, [review of Zaimov]. Slavic Review 31: 499.

- ^ Georgi Mitrinov, Contributions of the Sudzhov family to the preservation of Bulgarian cultural and historic heritage in Vardar Macedonia, Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, language; Bulgarian, Journal: Българска реч. 2016, Issue No: 2, pp. 104–112.

- ^ Угриновска-Скаловска, Радмила. Записи и летописи. Maкедонска книга, Скопје 1975. стр. 43–44.

- ^ Мошин, Владимир. Битољска плоча из 1017. год. // Македонски jазик, XVII, 1966, с. 51–61

- ^ Заимов, Йордан. Битолският надпис на цар Иван Владислав, самодържец български. Епиграфско изследване, София 1970, [review of Zaimov]. Slavic Review 31: 499.

- ^ Georgios Velenis, Elena Kostić (2016). Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress of Byzantine Studies: Thematic Sessions of Free Communications. Belgrade: The Serbian National Committee of AIEB and the contributors 2016. p. 128. ISBN 978-86-83883-23-3.

- ^ "Тоя субект се определя от сравнително ясно очертаната дата SФКВ (6522) от сътворението на света, или 1014 г. от новата ера, когато става поражението на Самуиловите войски при Беласица (на 29 юли)." "That subject is determined by the relatively clearly defined date SФKВ (6522) from the creation of the world, or 1014 of the new era, when the defeat of Samuel's troops at Belasitsa (on July 29) took place." in Йордан Заимов, Василка Тъпкова-Заимова (1970) Битолски надпис на Иван Владислав самодържец български. Старобългарски паметник от 1015-1016 година. Изд-во на Българската Академия на науките, стр. 28.

- ^ "Наспроти Коцо кој смета дека на ред 11 немало година,17 Мошин и Заимов овде ја читаат 6522 (1013/1014) г. макар Мошин да признава дека „годината е излижана“. (In English: Contrary to Koco, who believes that there was no year on line 11, Moshin and Zaimov read here 6522 (1013/1014), although Moshin admitted that "the year has been rubbed".) in Stojkov, Stojko (2014). Битолската плоча. Goce Delčev University. p. 82.

- ^ Битольская надпись Иоанна Владислава была создана, как считается, в 1015–1016 гг. (издание: Попконстантинов, Тотоманова 2014: 40–41, илл. 28а, 30). Однако, поскольку цифирь в надписи утрачена (см. Попконстантинов, Тотоманова 2014: илл. 28а, 30; см. затем примеч. 6 к этой статье), представляется более правильным датировать надпись временем правления Ивана Владислава, который упомянут в этой надписи как действующий самодержец, в сочетании с глагольной формой настоящего времени: 1015–1018 гг. (In English: "The Bitola inscription of John Vladislav was created, it is believed, in 1015–1016. (edition: Popkonstantinov, Totomanova 2014: 40–41, ill. 28a, 30). However, since the numbers in the inscription have been lost (see Popkonstantinov, Totomanova 2014: ill. 28a, 30; see then note 6 to this article), it seems more correct to date the inscription to the reign of Ivan Vladislav, who is mentioned in this inscription as the current autocrat, combined with the present tense verb form: 1015–1018.") in "Новые данные по истории древнеболгарского языка в эпиграфике Первого болгарского царства", 2023, Кирило-Методиевски студии 33:63-80. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1109461

- ^ "Mihajlovski gives the following measurements of the marble slab: "92cm long, 58cm wide and 55cm thick" (p. 17) and puts the inscription on the marble block in its historical context, i.e. the reign of Jovan Vladislav." in Sebastian Kempgen: A Superscript for the Bitola Inscription. Draft paper, p. 4, 12, May 2023. Bamberg University, Germany.

- ^

- Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009 ISBN 0810855658, pp. 194–195. "Bulgarian scholars have treated Samuel's rule as a continuation of the so-called First Bulgarian Tsardom, whose eastern part fell to Byzantium in 871. They have also referred to evidence such as John Vladislav's inscription found in Bitola, where the tsar is described as Bulgarian by birth."

- "However, John Vladislav was able to renovate and strengthen the fortifications of an alternative base, Bitola, commemorating the work with an inscription. Moreover, Basil's eighty-eight-day siege of Pernik ended in failure and heavy losses, while his siege of Kastoria, in late spring or summer 1017, was also unsuccessful." New Cambridge Medieval History, volume 3, ISBN 9780521364478, page 600.

- "An early example of the Cyrillic script, this inscription, carved in 1016, commemorates the refurbishment of the fortress of Bitolja (Macedonia) by John Vladislav, brother of the Bulgarian king Samuel, after the latter had been decisively defeated by Basil II." Mango, Cyril ed. (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. OUP Oxford. ISBN 0-19-814098-3, p. 238.

- "John Vladislav proclaimed himself Emperor of the Bulgarians, a title mentioned in an inscription dated to 6522 (ad 1014/5)." Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250], Cambridge medieval textbooks, Florin Curta, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-81539-8, p. 246.

- Basil II and the governance of Empire (976–1025), Oxford studies in Byzantium, Catherine Holmes, Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-927968-3, pp. 56–57. "...and the fourth (epigraph) inscribed in Cyrillic rather than Greek letters, to the strengthening of another fortress, this time at Bitola in western Macedonia by John Vladislav, the Bulgarian tsar, also dated, although with rather less certainty, to 1015."

- "The most extreme among the many illustrative examples of this scientific ethically questionable fact is probably the way in which an inscription found in Bitola in 1956 from the early eleventh century on Tsar Ivan Vladislav was dealt by the Yugoslav Macedonian authorities." Das makedonische Jahrhundert: von den Anfängen der nationalrevolutionären Bewegung zum Abkommen von Ohrid 1893–2001; ausgewählte Aufsätze, Stefan Troebst, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2007, ISBN 3-486-58050-7, S. 414.

- "Gabriels Nachfolger, Ioannes Vladislav (1015–1018), nach der Bitola - Inschrift ein gebürtiger Bulgare und „Enkel von Nikola und Rhipsime" (In English: Gabriel's successor, Jonnes Vladislav (1015–1018), according to the Bitola inscription a native Bulgarian and "grandson of Nikola and Rhipsime".) in War and Warfare in Byzantium: The Wars of Emperor Basil II Against the Bulgarians (976–1019), in Krieg und Kriegführung in Byzanz: Die Kriege Kaiser Basileios II. Gegen die Bulgaren (976–1019)], Paul Meinrad Strässle, Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar 2006, ISBN 341217405X, p. 159.

- "Славянское население Македонии в средние века ощущало и именовало себя болгарами, что отражалось и в царских титулах даже тогда, когда столицами болгарского государства становились македонские города Охрид и Преспа. Об этом красноречиво говорит, в частности, известная Битольская надпись властителя Ивана-Владислава, в которой он именует себя "царем болгар". (In English: The Slavic population of Macedonia in the Middle Ages felt and called themselves Bulgarians, which was reflected in the royal titles even when the Macedonian cities of Ohrid and Prespa became the capitals of the Bulgarian state. This is eloquently evidenced, in particular, by the famous Bitola inscription of ruler Ivan Vladislav, in which he calls himself "tsar of the Bulgarians.") in Г. Г. Литаврин, Прошлое и настоящее Македонии в свете современных проблем. в Македония: проблемы истории и культуры, редактор д-р ист. наук Р.П. Гришина. Институт славяноведения, Российская Академия Наук, Москва, ISBN 5-7576-0087-X, 1999 г.

- "Един от паметните моменти в този период е кратковременното управление на Йоан (Иван Владислав), племенник на цар Самуил, който управлява до 1018 г., след като е убил през 1015 г. братовчед си Гаврил Радомир в една семейна драма, която остава необяснена. Иван Владислав става прочут в българската история с надписа, който издига в Битоля." (In English: One of the memorable moments of this period is the short-lived reign of John (Ivan Władysław), a nephew of King Samuel, who ruled until 1018, after having murdered his cousin Gavril Radomir in 1015 in a family drama that remains unexplained. Ivan Vladislav became famous in Bulgarian history with the inscription he erected in Bitola.") in Василка Тъпкова-Заимова, Битолския надпис, стр. 42-46 в (Не)познатата проф. Василка Тъпкова-Заимова. Редактор: Проф. д.и.н. Рая Заимова, Институт за балканистика с център по тракология, Българска академия на науките. 2020, Studia balcanica No. 34.

- "Из њих потиче и једини сачувани изворни споменик изражавања етничке самосвести, такозвани Битољски натпис. Јован Владислав је дао да се на њему уклеше да је он „Бугарин родом“. После уништења Самуилове државе долази до кризе, мада не и до нестајања, друштвене елите која је била носилац традиција Бугарског царства. То ће етногенетске процесе успорити, и оставити простор за релативно безболну имплементацију неке довољно сличне словенске традиције, као што је она српске средњовековне државе." (In English: The only preserved original monument of ethnic self-awareness, the so-called Bitola inscription, originates from them. Jovan Vladislav had it engraved that he was a "Bulgarian native". After the destruction of Samuel's state, there is a crisis, although not the disappearance, of the social elite that was the bearer of the traditions of the Bulgarian Empire. This will slow down the ethnogenetic processes, and leave room for a relatively painless implementation of some sufficiently similar Slavic tradition, such as that of the Serbian medieval state.") in Срђан Пириватрић, „Самуилова држава. Обим и карактер", Византолошки институт Српске академије науке и уметности, посебна издања књига 21, Београд, 1997, стр. 196.

- Anmerkungen: (2) In der altbulgarischen Inschrift von Bitola von 1016 (Zaimov–Zaimova, Bitolski nadpis; Božilov in: KME I [1985] 196–198) wird dieser Ivan Vladislav – wörtlich als "Sohn des Aaron, des Bruders des Samuel" (l. 7f.) bezeichnet. (In English: Notes: (2) In the Old Bulgarian inscription from Bitola of 1016 (Zaimov–Zaimova, Bitolski nadpis; Božilov in: KME I [1985] 196–198) where Ivan Vladislav is literally referred to as "son of Aaron, brother of Samuel" (l. 7f.).) Ivan Vladislav. In Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit (2013). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- Иван Микулчиќ, Средновековни градови и тврдини во Македонија. (Македонска академија на науките и уметностите — Скопје, 1996), стр. 140–141. "Во прилог на горното мислење зборува и текстот на т.н. Битолска плоча подигната од Јован Владислав во 1016/17 година. Тој „го обновил градот Битола” (Ј. Заимов 1970, 1—160)." (In addition to the above opinion speaks the text of the so-called Bitola plate erected by Jovan Vladislav in 1016/17. He "renewed the city of Bitola" (J. Zaimov 1970, 1—160).)

- "...Ivan Vladislav, who in an inscription dated 1015–16 called himself "autocrat of the Bulgarian tsardom". Moreover, the inscription clearly describes him as a "native-born Bulgarian", which is unambiguous evidence that the awareness of constituting a natio had by then been fully established among the empire's political and cultural elite." in Eduard Mühle (2023) Slavs in the Middle Ages Between Idea and Reality. Brill, ISBN 9789004536746,p. 163.

- Henrik Birnbaum, Aspects of the Slavic Middle Ages and Slavic Renaissance culture, Peter Lang, 1991, ISBN 9780820410579, p. 540.

- Stefan Rohdewald (2022) Sacralizing the Nation Through Remembrance of Medieval Religious Figures in Serbia, Bulgaria and Macedonia, Vol. 1, ISBN 9789004516335, p. 69.

- Roumen Daskalov (2021) Master Narratives of the Middle Ages in Bulgaria, East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450-1450, BRILL, pp. 226-227.

- Dennis P. Hupchick, The Bulgarian-Byzantine Wars for Early Medieval Balkan Hegemony: Silver-Lined Skulls and Blinded Armies, Springer, 2017, p. 314.

- Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History, Volume 1, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 9783034301961, p. 245.

- Chris Kostov (2010) Contested Ethnic Identity. he Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996. Peter Lang, p. 51.

- Ivan Biliarsky, Word and Power in Mediaeval Bulgaria, Volume 14 of East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, BRILL, 2011, p. 215.

- Robert Mihajlovski (2021) The Religious and Cultural Landscape of Ottoman Manastır. Handbook of Oriental Studies, BRILL, p. 18.

- David Marshall Lang (1976) The Bulgarians. From Pagan Times to the Ottoman Conquest. Westview Press, ISBN 9780891585305, p. 79.

- ^ Битолската плоча: „помлада е за околу 25 годни од Самуиловата плоча...[ок. 1018 г.] Направена е по заповед на Јоан Владислав, еден од наследниците на Самуила. ...Истакнувањето на бугарското потекло од страна на Јоан Владислав е во согласност со настојувањето на Самуиловиот род да се поврзе со државноправната традиција на Симеоновото царство. Од друга страна, и западни и византиски писатели и хроничари, сите жители на царството на Петар [бугарски цар, владее од 927 до 969 г.], наследникот на бугарскиот цар Симеон, ги наречувале Бугари." Дел од содрината на плочата, според преводот на Скаловска:„Овој град [Битола] се соѕида и се направи од Јоан самодржец [цар] на бугарското (блъгарьскаго) цраство... Овој град (крепост) беше направен за цврсто засолниште и спасение на животот на Бугарите (Блъгаромь)... Овој цар и самодржец беше родум Бугарин (Блъгарїнь), тоест внук на благоверните Никола и Рипсимија, син на Арона, постариот брат на самодржавниот цар Самуил..." (Р.У. Скаловска, Записи и летописи. Скопје 1975. 43–44.) The Bitola inscription: "it is about 25 years younger than Samuel's inscription... [approx. 1018] It was made by order of John Vladislav, one of the heirs of Samuil. ...The highlighting of the Bulgarian origin by Ioan Vladislav is in accordance with the effort of Samuel's family to connect with the legal tradition of Simeon's kingdom. On the other hand, both Western and Byzantine writers and chroniclers called all the inhabitants of the kingdom of Peter [Bulgarian emperor, reigned from 927 to 969 AD], the successor of the Bulgarian emperor Simeon, Bulgarians." Part of the content of the tablet, according to the translation of Skalovska: "This city [Bitola] was built and made by John the autocrat [king] of the Bulgarian (Bulgarian) kingdom... This city (fortress) was made for a strong refuge and salvation of the life of the Bulgarians (Bulgarians).. This king and autocrat was born Bulgarian (Blăgarin), that is, the grandson of the pious Nikola and Ripsimia, the son of Arona, the elder brother of the autocratic king Samuel..." (R.U. Skalovska, Chronicles. Skopje 1975. 43- 44.)

- ^ Horace Lunt, Review of "Bitolski Nadpis na Ivan Vladislav Samodurzhets Bulgarski: Starobulgarski Pametnik ot 1015–1016 Godina" by Iordan Zaimov and Vasilka Zaimova, Slavic Review, vol. 31, no. 2 (Jun. 1972), p. 499

- ^ Robert Mathiesen, The Importance of the Bitola Inscription for Cyrillic Paleography, The Slavic and East European Journal, 21, Bloomington, 1977, 1, pp. 1–2.

- ^ ΚΟΣΤΙΤΣ, ΕΛΕΝΑ (2014). "ΜΟΡΦΟΛΟΓΙΑ ΤΗΣ ΚΥΡΙΛΛΙΚΗΣ ΓΡΑΦΗΣ ΣΤΙΣ ΕΠΙΓΡΑΦΕΣ ΑΠΟ ΤΗΝ ΕΜΦΑΝΙΣΗ ΤΗΣ ΕΩΣ ΤΑ ΤΕΛΗ ΤΟΥ 12ΟΥ ΑΙΩΝΑ" (PDF). Retrieved July 24, 2024.

- ^ Georgios Velenis, Elena Kostić (2016). Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress of Byzantine Studies: Thematic sessions of free communications (PDF). Belgrade: The Serbian National Committee of AIEB and the contributors 2016. p. 128. ISBN 978-86-83883-23-3.

- ^ Georgios Velenis, Elena Kostić (2017). Texts, Inscriptions, Images: The Issue of the Pre-Dated Inscriptions in Contrary with the Falsified. The Cyrillic Inscription from Edessa. Sofia: Институт за изследване на изкуствата, БАН. p. 117. ISBN 978-954-8594-65-3.

- ^ Mitko B. Panov, The Blinded State: Historiographic Debates about Samuel Cometopoulos and His State (10th–11th Century); BRILL, 2019, ISBN 900439429X, p. 74.

- ^ Стојков, Стојко (2014) Битолската плоча – дилеми и интерпретации. Во: Самуиловата држава во историската, воено-политичката, духовната и културната традиција на Македонија, 24–26 октомври 2014, Струмица, Македонија.

- ^ Ристо Бачев, Битолска плоча - веродостоен паметник или подметнат фалсификат. БИТОЛСКА_ПЛОЧА_ВЕРОДОСТОЕН_ПАМЕТНИК_ИЛИ_ПОДМЕТНАТ_ФАЛСИФИКАТ_2020_ сп. Снежник, бр. 7528, 2020.

- ^ "Најголема слабост на теоријата за датирање во XIII в. се јавува секако невоможноста да се направи смислена реконструкција на натписот и на спомнатите личности во него. Според тоа без да се смета целосно за затворено прашање засега датирањето на натписот во времето на Јован Владислав се јавува најаргументирано." (In English: The greatest uncertainty of the dating theory from the XIII century is the impossibility of making a meaningful reconstruction of the inscription and the persons mentioned in it. Therefore, without considering it a completely closed question, the dating of the inscription from the time of Ivan Vladislav appears to be the most well-argued for now.) in Stojkov, Stojko (2014). Битолската плоча. Goce Delčev University. p. 85.

- ^ "Although the inscription is of exceptional interest, the first study that attempted to fill in the missing text, was carried out by Vladimir Mošin only one decade after it was brought to light. Since, it has been the subject of studies of numerous researchers. Most of them reckon that the inscription is the last written source of the First Bulgarian State with an accurate dating..." For more see: Elena Kostić, Georgios Velenis, New Interpretation about the Content of the Cyrillic Inscription from Bitola. 23rd International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Belgrade, 22–27 August 2016.

- ^ Paul Stephenson, The legend of Basil the Bulgar-slayer, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-81530-4, p. 30.

- ^ Dennis P. Hupchick, The Bulgarian-Byzantine Wars for Early Medieval Balkan Hegemony: Silver-Lined Skulls and Blinded Armies, Springer, 2017, ISBN 3319562061, p. 314.

- ^ "Най-сетне (според Пириватрич) Битолският надпис показва, че Иван Владислав се счита за българин и счита своите поданици за българи...Битолският надпис е пример за своеобразно изразяване на етническо съзнание." (Finally (per Pirivatric) the Bitola inscription shows that Ivan Vladislav considered himself a Bulgarian and considered his subjects Bulgarians... The Bitola inscription is an example of a particular expression of ethnic consciousness.) Румен Даскалов, Историографски спорове за средновековието - българо-сръбски, българо-македонски. Унив. издателство „Св. Климент Охридски“, 2024, ISBN 9789540759128, стр. 310.

- ^ "Samuel's kingdom was indeed a Bulgarian state, whose people the Greeks regarded as Bulgars. Paul Stephenson states in carefully measured phrasing, that during the period of peace with Samuel, (1005-1014) "on my reading of the evidence, [Emperor) Basil (II) recognized an independent realm known as Bulgaria." Besides this, Ivan Vladislav, the last Tsar, in an inscription found on Bitola castle, intended it as "a refuge for the Bulgars." He declared himself "autocrat of the Bulgars" and "Bulgarian by birth"...By writing, as Boškoski does, about the Macedonians", "the Macedonian Tsar", and the "Macedonian defence", he merely creates, in an otherwise valuable study, an ahistorical artifact to serve present day nationalist sentiment. Pirivatrić, a Serbian author, avoids the issue by claiming that modern notions of national identity are inappropriate to the era of the kometopuli, but Bulgarian national consciousness was nonetheless vibrant. It was to remain so throughout the 11th century." For more see: Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History, Volume 1, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 1443888435, p. 245.

- ^ Ivan Biliarsky, Word and Power in Mediaeval Bulgaria, Volume 14 of East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, BRILL, 2011, ISBN 9004191453, p. 215.

- ^ Room, Adrian, Placenames of the world: origins and meanings of the names for 6,600 countries, cities, territories, natural features, and historic sites, Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, ISBN 0-7864-2248-3, 2006, p. 60.

- ^ Robert Mihajlovski (2021) The Religious and Cultural Landscape of Ottoman Manastır. Handbook of Oriental Studies, BRILL, p. 18; ISBN 900446526X.

- ^ Grant Schrama, Bulgarian Perceptions of East Romans in The Routledge Handbook of Byzantine Visual Culture in the Danube Regions, 1300-1600, Routledge, 2024, ISBN 9780367639549. "Compared to our East Roman sources, the perspective from Bulgaria itself is more limited. The sources are not as extensive but still offer a glance into how Bulgarian authors viewed their East Roman counterparts and highlighted their own communal identity. One of the most common designations for the East Romans was "Greeks", instead of Romaioi, with the emperors called "tsars". (...) Another inscription of Tsar Ivan Vladislav (r. 1015–18), located in Bitolja and dated to 1016, mentions the "Greek army of Tsar Basil", referencing Emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025)."

- ^ J. Pettifer ed., The New Macedonian Question, St Antony's Series, Springer, 1999, ISBN 0230535798, p. 75.

- ^ Исправена печатарска грешка, Битола за малку ќе се претставуваше како бугарска. Дневник-online, 2006.Archived February 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Битолският надпис в bTV Репортерите на 19 и 20 юни. 17.06.2021, bTV.

References

[edit]- Божилов, Иван. Битолски надпис на Иван Владислав // Кирило-методиевска енциклопедия, т. І, София, 1985, с. 196–198. (in Bulgarian)

- Бурмов, Александър. Новонамерен старобългарски надпис в НР Македония // сп. Пламък, 3, София, 1959, 10, с. 84–86. (in Bulgarian)

- Заимов, Йордан. Битолски надпис на Иван Владислав, старобългарски паметник от 1015–1016 // София, 1969. (in Bulgarian)

- Заимов, Йордан. Битолският надпис на цар Иван Владислав, самодържец български. Епиграфско изследване // София, 1970. (in Bulgarian)

- Заимов, Йордан. Битольская надпись болгарского самодержца Ивана Владислава, 1015–1016 // Вопросы языкознания, 28, Москва, 1969, 6, с. 123–133. (in Russian)

- Мошин, Владимир. Битољска плоча из 1017. год. // Македонски jазик, XVII, Скопје, 1966, с. 51–61 (in Macedonian)

- Мошин, Владимир. Уште за битолската плоча од 1017 година // Историја, 7, Скопје, 1971, 2, с. 255–257 (in Macedonian)

- Томовић, Г. Морфологиjа ћирилских натписа на Балкану // Историјски институт, Посебна издања, 16, Скопје, 1974, с. 33. (in Serbian)

- Џорђић, Петар. Историја српске ћирилице // Београд, 1990, с. 451–468. (in Serbian)

- Mathiesen, R. The Importance of the Bitola Inscription for Cyrilic Paleography // The Slavic and East European Journal, 21, Bloomington, 1977, 1, pp. 1–2.

- Угринова-Скаловска, Радмила. Записи и летописи // Скопје, 1975, 43–44. (in Macedonian)

- Lunt, Horace. On dating Old Church Slavonic bible manuscripts. // A. A. Barentsen, M. G. M. Tielemans, R. Sprenger (eds.), South Slavic and Balkan linguistics, Rodopi, 1982, p. 230.

- Georgios Velenis, Elena Kostić, (2017). Texts, Inscriptions, Images: The Issue of the Pre-Dated Inscriptions in Contrary with the Falsified. The Cyrillic Inscription from Edessa.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Zaimov claims that the paleographer Hristo Kodov had the idea for the existence of the first, lost row. There are several reasons for this suggestion. First of all, an initial cross is missing, which was inevitable in such inscriptions then. Also, a verb and a subject are stuck in the preserved first row of the inscription, and so the sentence begins with two present participles, making it incomplete. Last, the conjunction "же" in the second half of the third line introduces a new, second sentence, which reveals another side of the inscription's content, and cannot be a continuation of the first sentence.